Anger over job issues and fears among Dalits and Muslims contributed to the BJP’s loss, despite the party’s hopes that the Ram temple launch five months earlier would secure a significant victory.

India’s elections had not yet commenced, but columnists based in Delhi were already predicting the outcome of the most significant prize: Uttar Pradesh (UP), the northern state that is the country’s largest and sends the largest number of legislators to the national parliament. The state’s 80 members of parliament in a house of 543 often determine the fate of the national government.

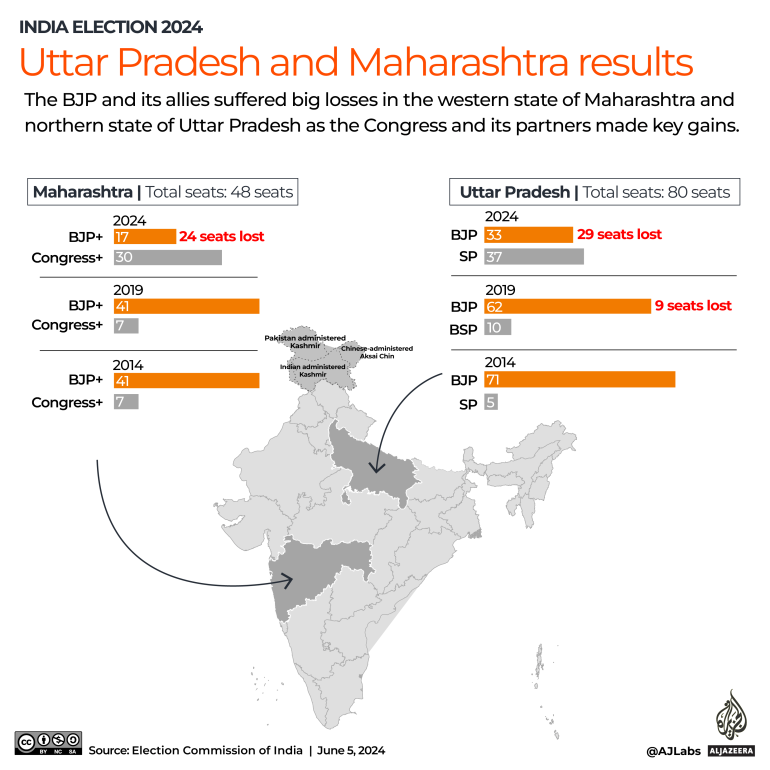

In 2014 and 2019, Uttar Pradesh played a pivotal role in shaping the fortunes of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), with Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party securing 71 and 62 seats respectively in those elections. Columnists confidently anticipated a repeat performance, considering it a foregone conclusion for the BJP.

However, Hakim Sahib, a full-time mendicant and part-time politician from Meerut, a city in western Uttar Pradesh (UP), expressed skepticism. “BJP will not secure more than 40 seats in UP as there is a strong undercurrent against the party,” he remarked.

Two months later, when the results were announced on June 4 following seven stages of staggered polling, Sahib’s foresight proved accurate, contrary to the expectations of the majority of pollsters who had predicted a BJP sweep in UP and across India.

As the election unfolded across the state, home to over 200 million people, it became evident that while Modi and the BJP maintained considerable influence, there was also a noticeable undercurrent of anger among many voters, including traditional supporters, stemming from high unemployment and inflation. The opposition INDIA alliance capitalized on this sentiment, cleverly turning a BJP campaign slogan aiming for 400 parliamentary seats into a narrative against the ruling party, suggesting that such a mandate could jeopardize the constitutional rights of historically disadvantaged communities like Dalits.

This sentiment translated into the outcome predicted by Sahib: The BJP secured only 33 seats, with its allies adding three more. Meanwhile, the regional Samajwadi Party, part of the Congress Party-led INDIA alliance, secured 37 seats, with the Congress itself winning an additional six seats. This result, coupled with losses in Maharashtra, compelled the BJP to seek alliance partners to form a government, falling short of a national majority on its own.

The discontent that culminated in this moment wasn’t limited to traditional BJP critics; even some ordinary voters who had contributed to its rise felt disillusioned.

The BJP spearheaded a campaign in 1992 that resulted in the demolition of the 16th-century Babri mosque in Ayodhya, Uttar Pradesh. On December 6 of that year, as images of the shrine being razed to the ground reverberated across India and beyond, Mohan found himself among the crowd at the site, participating in the destruction of the mosque.

In January of this year, Modi inaugurated a magnificent Ram temple at the very site in Ayodhya. According to ancient scriptures, Ayodhya is the birthplace of the Hindu deity Ram. This event, much like the 1992 demolition, garnered global attention and served as the starting point for Modi’s re-election campaign in 2024.

When interviewed in April, Mohan—who preferred not to disclose his last name—expressed his disillusionment with the BJP. He mentioned his unemployed son, who initially considered joining the Modi government’s program to send Indian workers to Israel as laborers during the conflict in Gaza but ultimately decided against it.

Mohan confidently asserted, “This time, the BJP will not come to power in the parliamentary elections. I will call you on June 4 to confirm this.”

While Mohan’s prediction was partially incorrect—the BJP is set to form the next government with its allies—there were notable setbacks for the party. For instance, in Faizabad, the constituency encompassing the Ram temple, the BJP faced defeat. Mohan’s sentiments echoed those shared by voters, including in Modi’s own parliamentary constituency of Varanasi.

The impact of his authority is evident in the extensive infrastructure development across the city: from a new highway leading to the airport to the rejuvenated banks of the Ganges and widened roads leading to Varanasi’s main attraction, the Kashi Vishwanath Temple.

However, according to Vishambhar Mishra, a professor at the city’s Indian Institute of Technology and the head of the Sankat Mochan Trust, these transformations have stripped the city of its unique identity.

“Varanasi used to be a city of narrow lanes and alleys. People could navigate these lanes from any starting point to reach the ghats for a dip in the Ganges,” he remarked. Despite numerous government pledges to clean up the Ganges, the river remains polluted—a contradiction he regularly highlights on the social media platform X.

During a boat ride on the Ganges, boatman Bhanu Chaudhary, who accompanied the writer, expressed, “There is widespread frustration among people due to lack of employment opportunities.” Chaudhary, a graduate, resorts to rowing boats for tourists as he struggles to find alternative employment.

This frustration was palpable on June 4. Although Modi secured victory in the seat, his margin was significantly reduced from 480,000 votes in 2019 to 152,000 this time. Many constituencies near Varanasi, which the BJP had hoped to win with Modi’s presence in the city, were won by the INDIA alliance.

People beat drums in front of a vehicle carrying a large garlanded portrait of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, the chief architect of the Indian constitution, as they celebrate his birth anniversary in Mumbai, India, April 14, 2024. Ambedkar, a Dalit, and a prominent Indian freedom fighter, outlawed discrimination based on caste. Analysts believed the Dalit move shifted away from the BJP in the just-concluded election [Rafiq Maqbool/AP Photo]

Observers suggest that the BJP’s own statements may have been the primary reason for the shift in voter allegiance.

The party’s slogan proclaiming that the BJP-led alliance would secure 400 seats unsettled many Dalits, who feared that the party might amend the constitution—drafted under the leadership of Dalit icon Bhimrao Ambedkar—to revoke their hard-earned protections, explained Inderjit Singh, a teacher in Gorakhpur, a city in northern Uttar Pradesh. “As a result, many seats slipped away from the BJP’s grasp,” he noted.

Initial data indicates that the opposition INDIA alliance effectively forged a coalition of Dalits, along with other traditionally marginalized communities—referred to as Other Backward Classes (OBCs) in India—and Muslims in various parts of the state.

Gautam Rane, a Dalit activist who campaigned against the BJP, asserted, “They want to change the constitution of India and stop job reservation.” However, the BJP has refuted any intentions of revoking benefits promised to Dalits in the constitution, including quotas in government jobs and educational institutions.

Rane noted that many Dalit voters had abandoned the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP), which historically led the community in UP, feeling it was too weakened to effectively challenge the BJP. Despite this, the BSP still secured 9 percent of the state’s vote but failed to win any constituencies, in contrast to its 10 seats in 2019.

Furthermore, Modi’s remarks targeting Muslims during the campaign—referring to them as “infiltrators”—energized the community, constituting almost 20 percent of UP’s population, to rally behind the opposition alliance, according to Nawab Hussain Afsar, the editor of an Urdu daily based in Lucknow, the state’s capital.